The Awkward Grace of Trying Again: Baby Steps, Mindfulness, and the Trauma of Being Helped

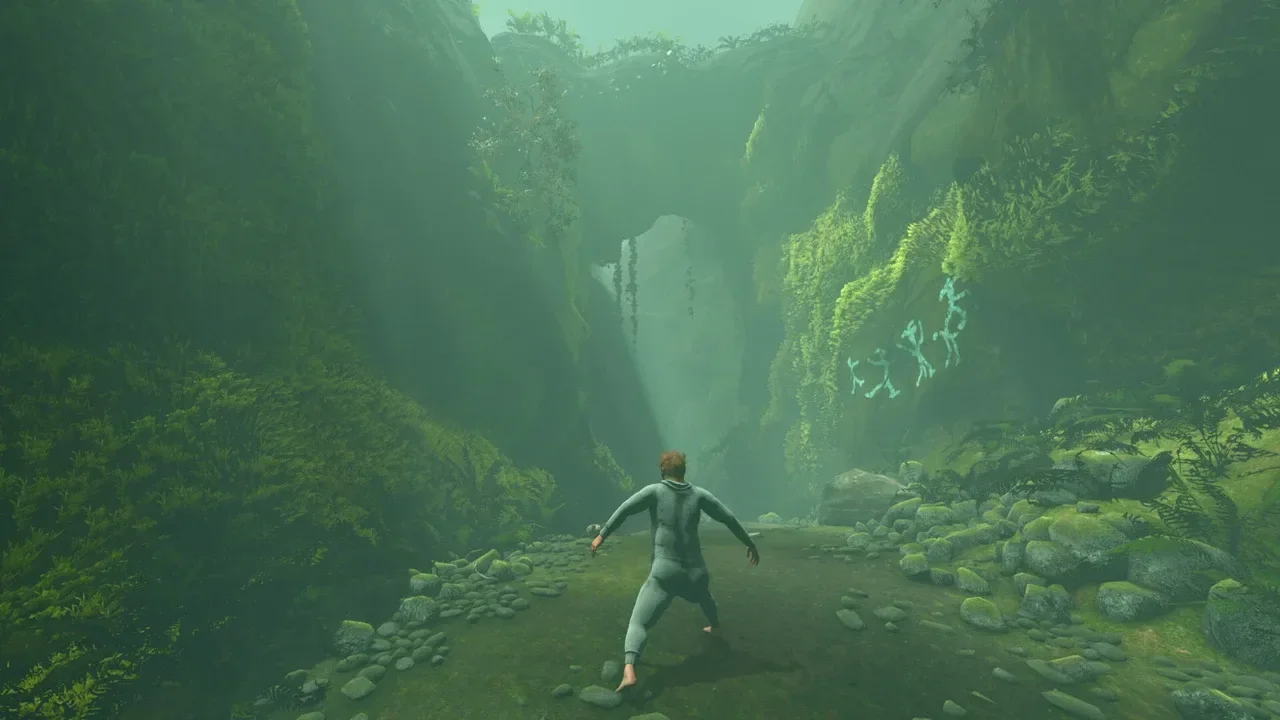

In Baby Steps, you control a man named Nate who can barely walk. Each leg has its own button, and every movement requires awkward precision. He stumbles, trips, grunts, and talks to himself as he climbs a mountain that seems to exist purely to humiliate him. It’s ridiculous. It’s frustrating. And somehow, it’s one of the most honest depictions of mindfulness I’ve ever seen.

Developed by Gabe Cuzzillo, Maxi Boch, and Bennett Foddy–the creators of QWOP and Getting Over It–Baby Steps is a physics-based “walking simulator” where simply taking a few steps feels like an accomplishment. It’s part comedy, part existential endurance test. There are no enemies, no new abilities to master, and no shortcuts. The challenge isn’t conquering the mountain; it’s staying present long enough to keep going.

Mindfulness When the Body Isn’t Safe

Traditional mindfulness practices often tell us to “sit still and notice the body.” But for someone with a trauma history, that can feel impossible. The body might not feel like a safe place to be. Sensations can carry memories, tension, or reminders of danger. Even something as simple as feeling your breath can trigger panic if your body has learned that stillness equals vulnerability.

For many trauma survivors, dissociation becomes a survival skill. You learn to live slightly outside yourself, watching life from a distance where it feels manageable. It’s not that you don’t want to be present; it’s that presence has cost you before.

Baby Steps quietly invites you back into the body, but in the safest way possible: through humor, through absurdity, through failure that carries no real consequence. You can’t move without noticing your body. Every shift of weight matters. If you lean too far forward, Nate collapses. If you rush, he tumbles down the hill, and you lose hours of progress. The game demands full awareness of every tiny motion, yet offers no comfort when you fail. It is mindfulness in its purest form: noticing what is happening without the guarantee that it will feel good.

The game doesn’t let you check out or move on autopilot. It keeps pulling you back into the immediate moment. To move, you have to feel—the timing, the balance, the rhythm. It’s clumsy and deliberate. The more you resist the body’s limits, the harder the fall. The more you cooperate with them, the steadier you become.

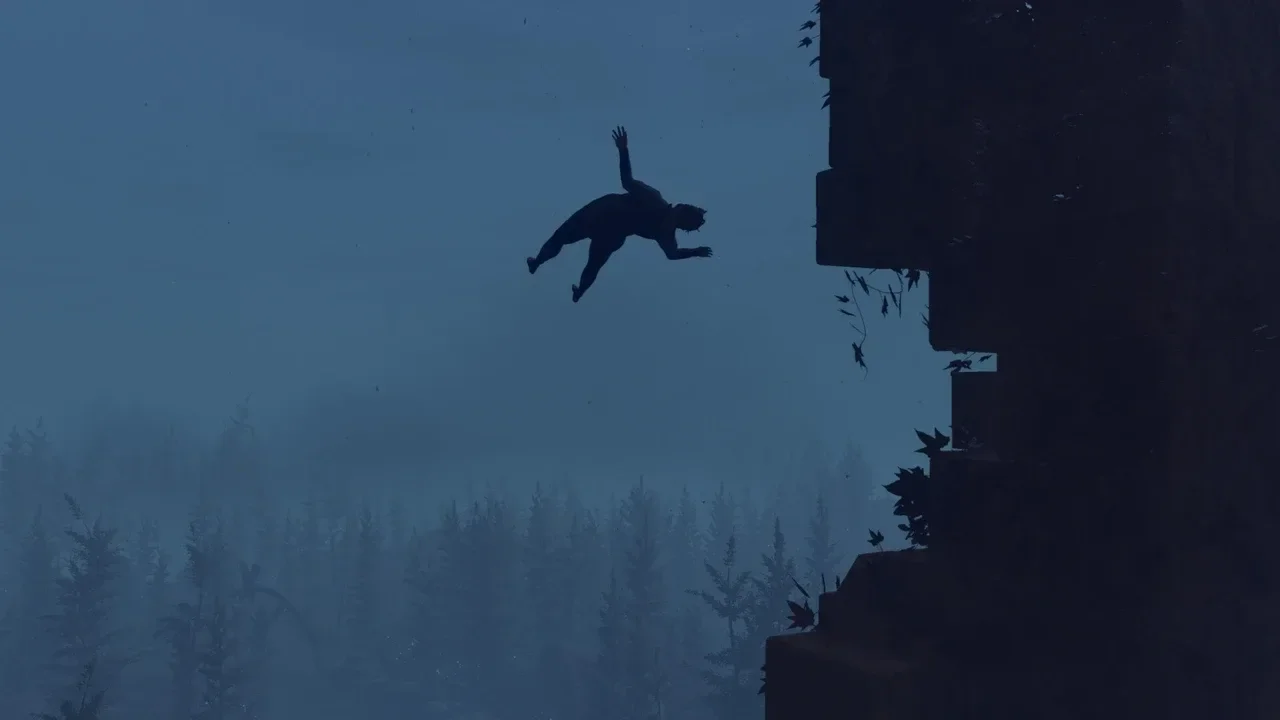

When Nate falls, the camera doesn’t cut away. It lingers. You see him lying there, limbs tangled. The fall is part of the experience. That’s what trauma-informed mindfulness asks of us too–to notice the fall without judgment and to remember that awareness doesn’t mean control.

The Slowness That Feels Like Safety

We live in a world that rewards speed, efficiency, and “moving on.” But trauma healing asks for something slower. It asks us to move at the pace of safety.

Baby Steps refuses to let you rush. You can’t sprint or skip ahead. The only way forward is slow, intentional progress. It mirrors how the nervous system learns to trust again: one careful step, one trusted connection, one moment of trying without collapsing.

When I watch Nate steady himself before a climb with sweat and mud stains adorning his onesie, I see what healing looks like. It’s not graceful. It’s cautious. It’s learning how to balance effort with rest.

When Help Feels Like a Threat

One of the most striking parts of Baby Steps is Nate’s attitude toward help. People in his world occasionally offer guidance or encouragement, but he mocks them. He brushes them off. He refuses to let anyone carry him, even when it’s clear he’s struggling.

That’s not laziness. That’s survival. For many people who have lived through trauma, accepting help can feel dangerous. Maybe help once came with strings attached. Maybe asking for care led to harm. So independence becomes armor, and self-reliance feels safer than vulnerability.

There’s a unique kind of exhaustion that comes from doing everything alone. You tell yourself it’s easier not to rely on anyone, but the cost is constant vigilance, and sometimes, you know you’re harming yourself by keeping everyone out. The body stays tense, the mind scans for threat, and rest starts to feel like risk. In that way, Nate’s refusal to lean on others becomes familiar. He isn’t just rejecting help; he’s protecting himself from the pain of needing something he believes won’t last.

That pattern shows up in trauma recovery. The moment someone offers support, the mind flares up with suspicion. What will they want in return? What happens if they leave? Even compassion can feel like a trap. Learning to accept help again isn’t about forcing trust; it’s about letting safety grow slowly, like testing your footing before taking a step.

Nate’s resistance to help isn’t selfishness; it’s self-protection. He doesn’t trust that being seen in his struggle will end well. The player feels that tension too: wanting him to accept support but understanding why he won’t.

Healing often looks the same. We want to trust others, but trust can’t be forced. Sometimes, mindfulness means simply noticing the part of you that tenses at kindness and giving it time.

The Discipline of Presence

If Baby Steps teaches anything, it’s that distraction has consequences. The moment you stop paying attention–answer a text, glance away, think too far ahead–you fall. The game forces the player into absolute presence. You have to feel each step, stay tuned to the rhythm of movement, and respond in real time, or you will fall and have to find your rhythm all over again.

That’s the heart of mindfulness: beginning again. You can’t plan three steps ahead in Baby Steps; you can only manage the one you’re taking. It becomes a strange kind of meditation where attention isn’t just encouraged, it’s required.

In trauma recovery, that same skill matters. The mind loves to time-travel, revisiting old pain or scanning for new danger. Relearning to stay here, even for a few seconds, can be a incredible act of healing.

Falling Without Failing

Every time Nate falls, the world doesn’t punish him. There’s no “game over.” You just pick yourself up and keep going. The mountain waits, patient and quiet.

That’s how healing works with the proper support. The goal isn’t to never fall again; it’s to know that the fall isn’t final. Each collapse teaches something about balance, timing, and limits. Mindfulness doesn’t erase difficulty, it lets you meet it with curiosity instead of shame.

The Courage to Try Again

What I love most about Baby Steps is that it doesn’t glorify perseverance. It just shows it. You fall, you groan, you mutter, and then, maybe out of frustration or hope, you stand up and try again. You don’t win anything for moving without falling for a long time either, you just get to keep going.

That’s what trauma recovery looks like in real life. There’s no single moment of enlightenment, no perfect balance you keep forever. There are only small, imperfect moments of trying and eventually, you realize that you’ve been making small progress all along.

Mindfulness, in that sense, isn’t about staying calm or centered. It’s learning how to be present with your own clumsy persistence. It’s recognizing that each unsteady step is still movement.

Learning to Be Carried

The hardest part of Baby Steps isn’t the walking. It’s the surrender–you will fail, you will lose progress, you will struggle. It’s realizing that gravity is not the enemy, that the same force that makes you fall also helps you stand.

Many games tempt you to “rage quit” after too many failures. They punish mistakes with defeat screens or take away your inventory or progress until you earn it back. Baby Steps doesn’t do that. It invites you to fail so completely, and so often, that failure becomes part of the rhythm. Falling is the story. You can’t progress without it.

That’s what makes it such an unexpected teacher. You stop trying to avoid mistakes and start getting curious about them. You begin to laugh when you fall instead of getting angry. That shift, from shame to curiosity, is exactly what trauma recovery asks of us.

In that is the greatest lesson the game offers: that healing isn’t about mastering control and becoming an island, but about learning that you don’t have to be an island and failure won’t ruin you.